First lines. Literature revels in them. But history? Archaeology? Paleoanthropology? What kind of first lines do we see in those subjects?

I started thinking about first lines recently – what is expected from first lines when one writes history and what form these first lines can take. In writing the history of material objects, I came to the conclusion that there is a strong tradition, realized or not, to begin with the discovery of that object. History and anthropology ties the object (say, a fossil) to a moment in time and it’s easy to use “discovery” to situate a narrative in a timeline of sorts.

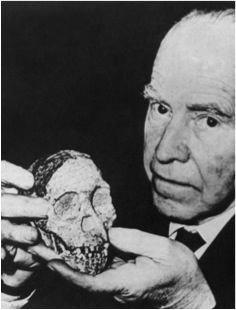

"Australopithecus" (the Taung Child) with its Raymond Dart. Raymond Dart Archive, courtesy of the University of Witwatersrand.

The development of human palaeontology has been marked by three essential stages: the discovery of Neanderthal Man in 1856, that of Pithecanthropus in 1891, and that of Australopithecus in 1925. Preface of Fossil Men (1957) by Boule and Vallois.

Discovery seems to be a comfortable trope and an easy beginning to talk about fossils. But I’m curious what other types of first lines could be out there.

The following is a completely haphazard collection of first lines, pulled from whatever literature, history, and anthropology was in easy reach of my desk. I was stuck by how deeply history of paleoanthropology is tied to the process and materiality of discovery. And just how differently first lines function between disciplines. (For those interested in Piltdown Man, check out Piltdown Man: Untangling One of the Most Infamous Hoaxes in Scientific History.)

LITERATURE

This is the saddest story I have ever heard. —Ford Madox Ford, The Good Soldier (1915)

Once upon a time and a very good time it was there was a moocow coming down along the road and this moocow that was coming down along the road met a nicens little boy named baby tuckoo. —James Joyce, A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (1916)

Mother died today. —Albert Camus, The Stranger (1942; trans. Stuart Gilbert)

It was a bright cold day in April, and the clocks were striking thirteen. —George Orwell, 1984 (1949)

There is a setting, an anticipation, an expectation, and a story in these.

ANTHROPOLOGY

This volume [Men of the Stone Age] is the outcome of an ever-memorable tour through the country of the men of the Old Stone Age. —Henry Fairfield Osborn, Men of the Old Stone Age, Their Environment, Life and Art, (1915.)

Les Hommes Fossiles has always ranked, and will doubtless long continue to rank, as the most comprehensive and authoritative general work on human palaeontology. – Maracellin Boule & Henri V. Vallois, Fossil Men (1957)

It is not so very long since Copernicus and Galileo first proved that the earth is only a satellite of the sun. – Henri Breuil & Raymond Lantier, The Men of the Old Stone Age (Palaeolithic & Mesolithic), (1959, translated by B.B. Rafter.)

There is a commitment to discovery or future discovery of fossils.

HISTORY

In the second century of the Christian era, the Empire of Rome comprehended the fairest part of the earth, and the most civilised portion of mankind. —Edward Gibbons The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire

The story of the Copernican Revolution has been told many times before, but never, to my knowledge, with quite the scope and object aimed at here. – Thomas Kuhn The Copernican Revolution, (1957.)