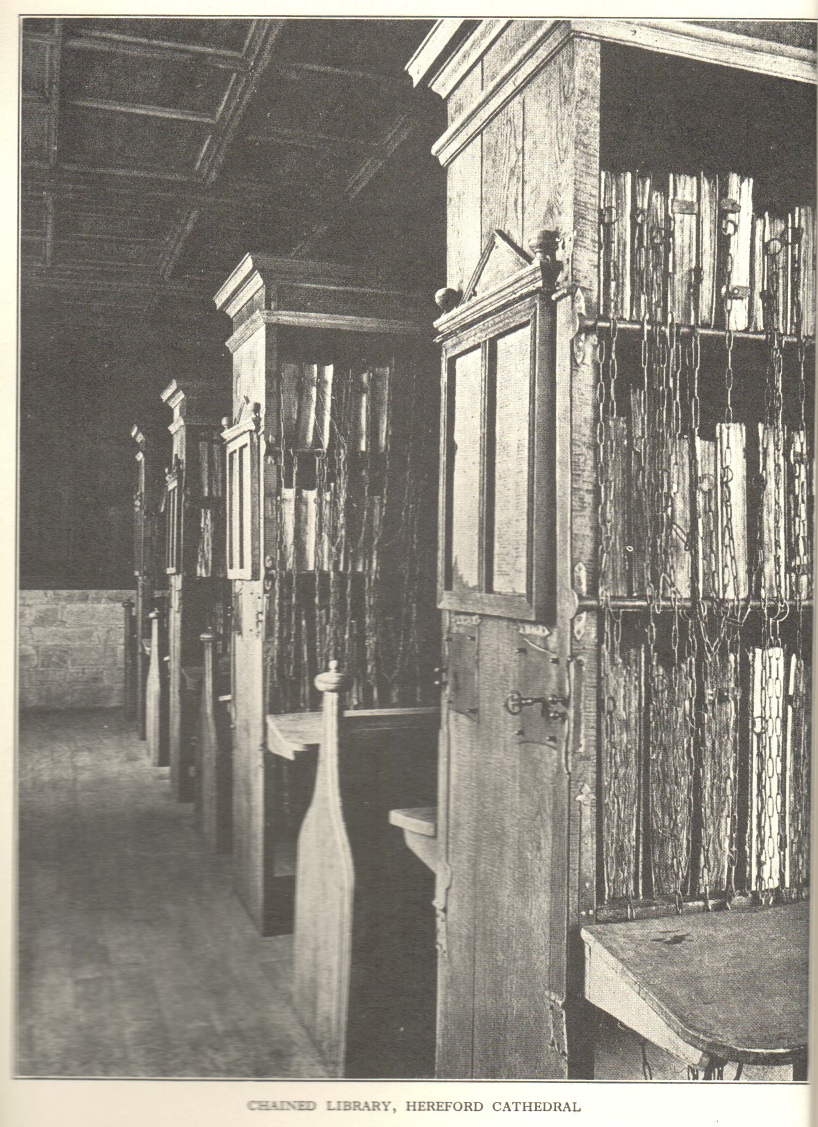

Chained Library, Hereford Cathedral. Frontpiece to The Chained Library: A Survey of Four Centuries in the Evolution of the English Library. (B.H. Streeter, 1931.)

The history of fossils is full of metaphors. The Book of Nature, missing links, and even the phylogenetic tree populate paleo-discourse to say nothing of the actual metaphors used in evolutionary studies like trellises and ladders, braided rivers, and Banyan trees. Metaphors have exceptional explanatory power. As the fossil record is an incomplete archive of evolution over the longe duree of deep geological time, the use of metaphor in writing about it is rather inescapable.

While paleo-studies draw on metaphors as explanatory devices, they offer other disciplines their own unique set of parallels. Evolution, particularly, becomes a mechanism for explaining change – one of the most powerful metaphors biology and paleo-studies could offer.

In the 1930s, fossil discoveries of “missing links” (like Piltdown, the Taung Child, and Peking Man) peppered discussions of evolution in media and public spheres. The broad narrative of human evolution, in particular, was told and re-told, and the popularity of the subject meant that its language wormed its way into rather unexpected places and unanticipated subjects.

Take, for example, Burnett Hillman Streeter’s work in the history of books. In 1931, Streeter compiled The Chained Library: A Survey of Four Centuries in the Evolution of the English Library. (Streeter was a fellow of the Queen’s College (Oxford) and of the British Academy.) Streeter was fascinated by the technological shifts in book storage – from chained libraries to the then-current library practices – and drew on the popularity, ubiquity, and power of the metaphor the evolution offered.

“Chaining, then, in ancient libraries is not an interesting irrelevance. The fact that some anthropoid ancestor began to employ his front paws for grasping instead of for walking conditioned the upright posture of man and his use of tools – and so his whole future development.”[1]

While the early twentieth-century scientific drama of “missing link” fossils might have been played out by a few, the metaphors of evolution – even evolution itself! – proved to have reach well-beyond paleo-research circles.

Group portrait of the Piltdown skull being examined. Piltdown was touted as a "Missing Link" in human evolution, before exposed as a hoax. Painting by John Cooke, 1915.

Sources

[1] Burnett Hillman Streeter, The Chained Library; a Survey of Four Centuries in the Evolution of the English Library. (New York: B. Franklin, 1970, 2nd edition), p. xiii.