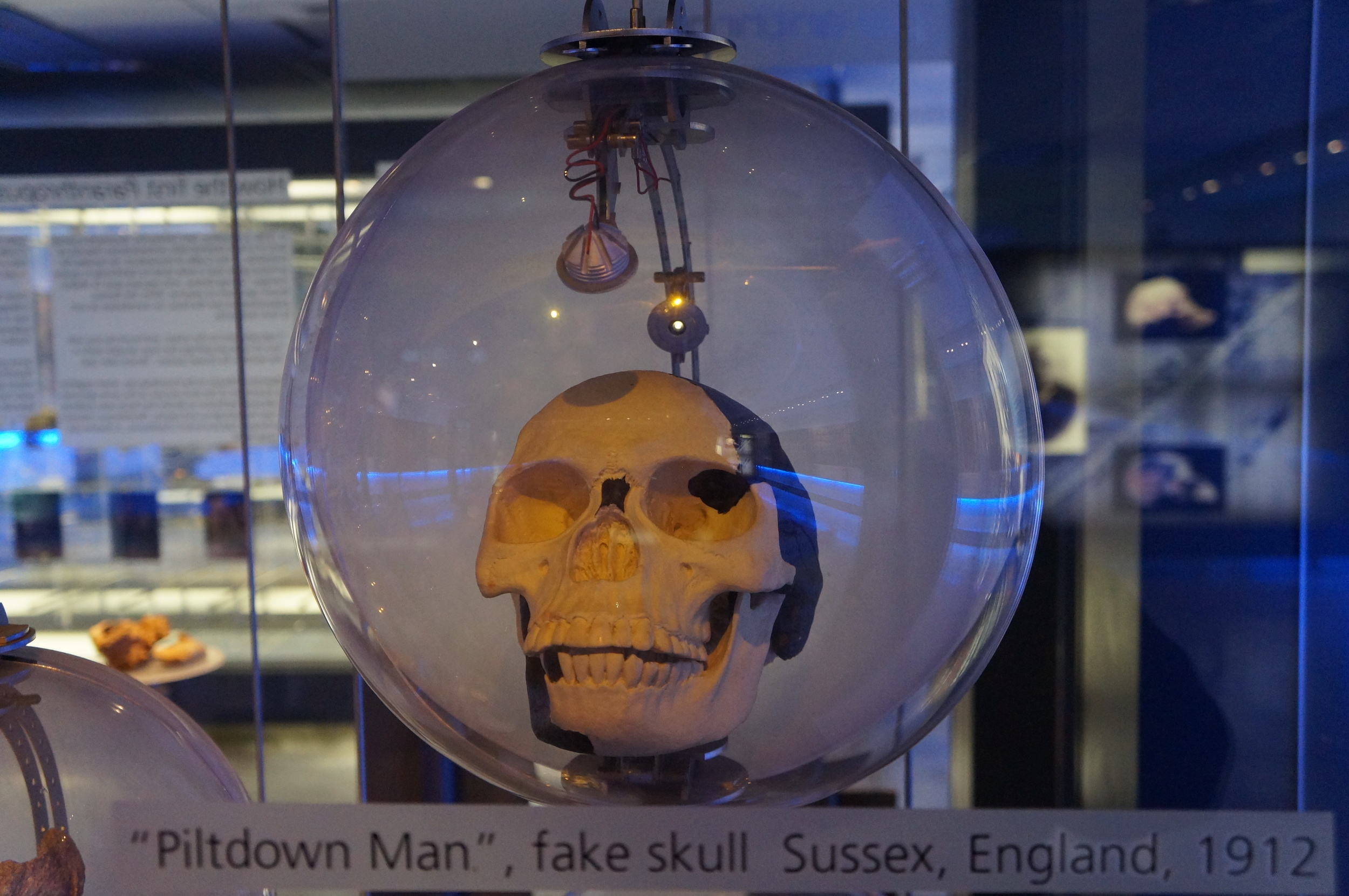

Few scientific forgeries have captured the scientific and public imaginations as completely as that of the 1912 Piltdown Man hoax. While examples of blatant fraud can be found in many scientific disciplines over several centuries, out-and-out forgeries and hoaxes prove to be relatively rare and comparatively short-lived. The Piltdown Man is, perhaps, one of the most-studied but least-resolved episodes in twentieth-century paleoanthropology.[1]

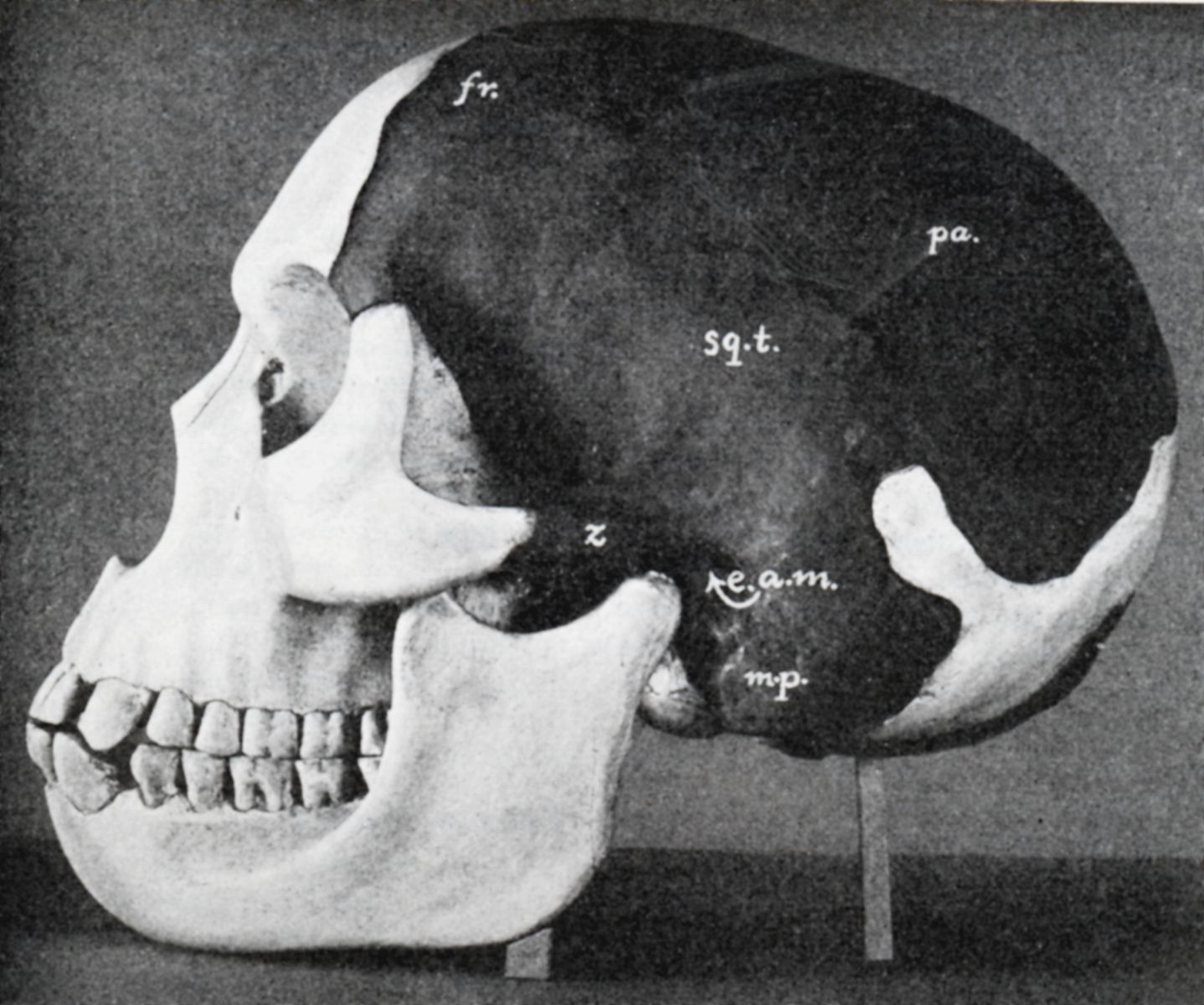

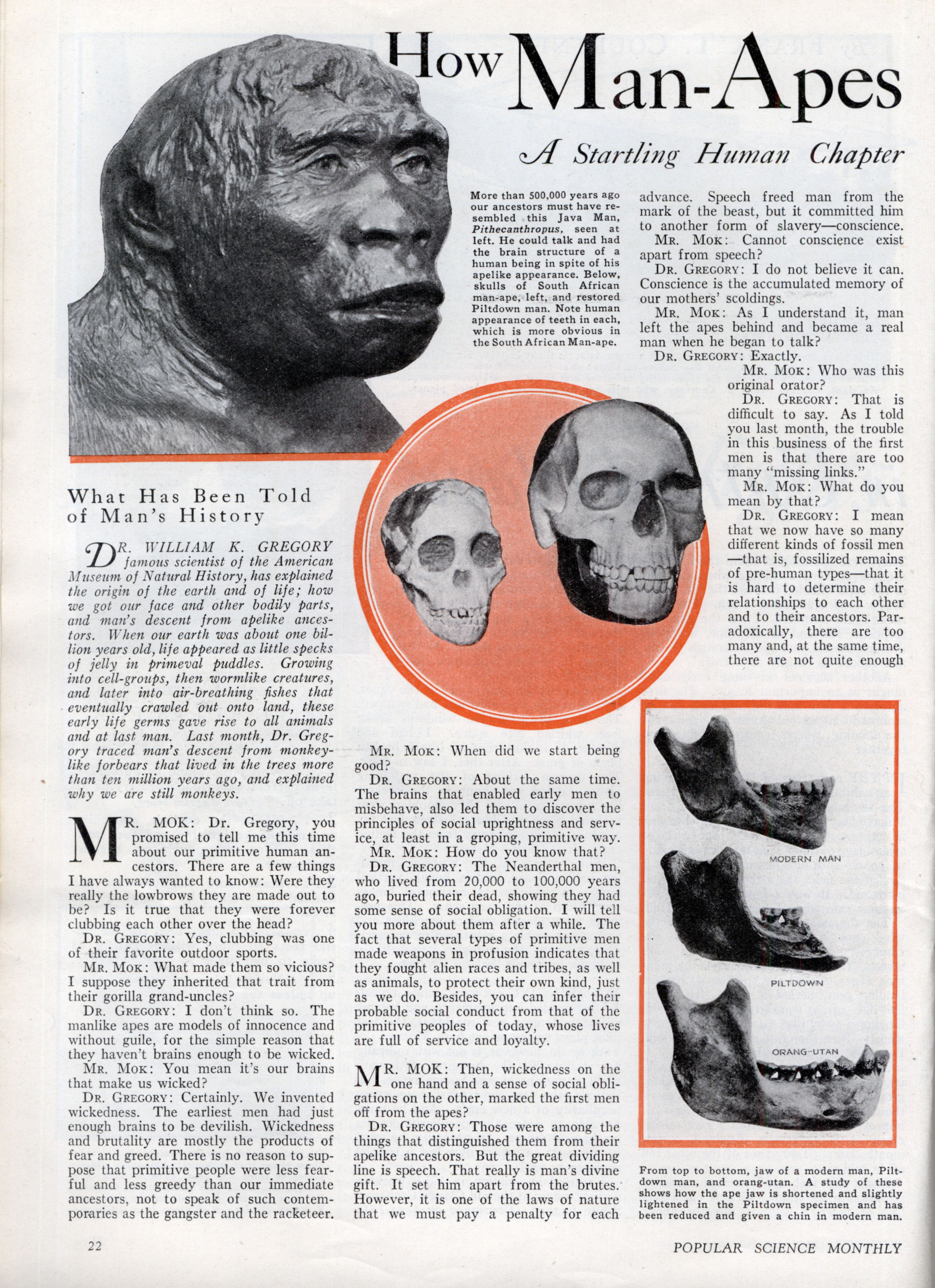

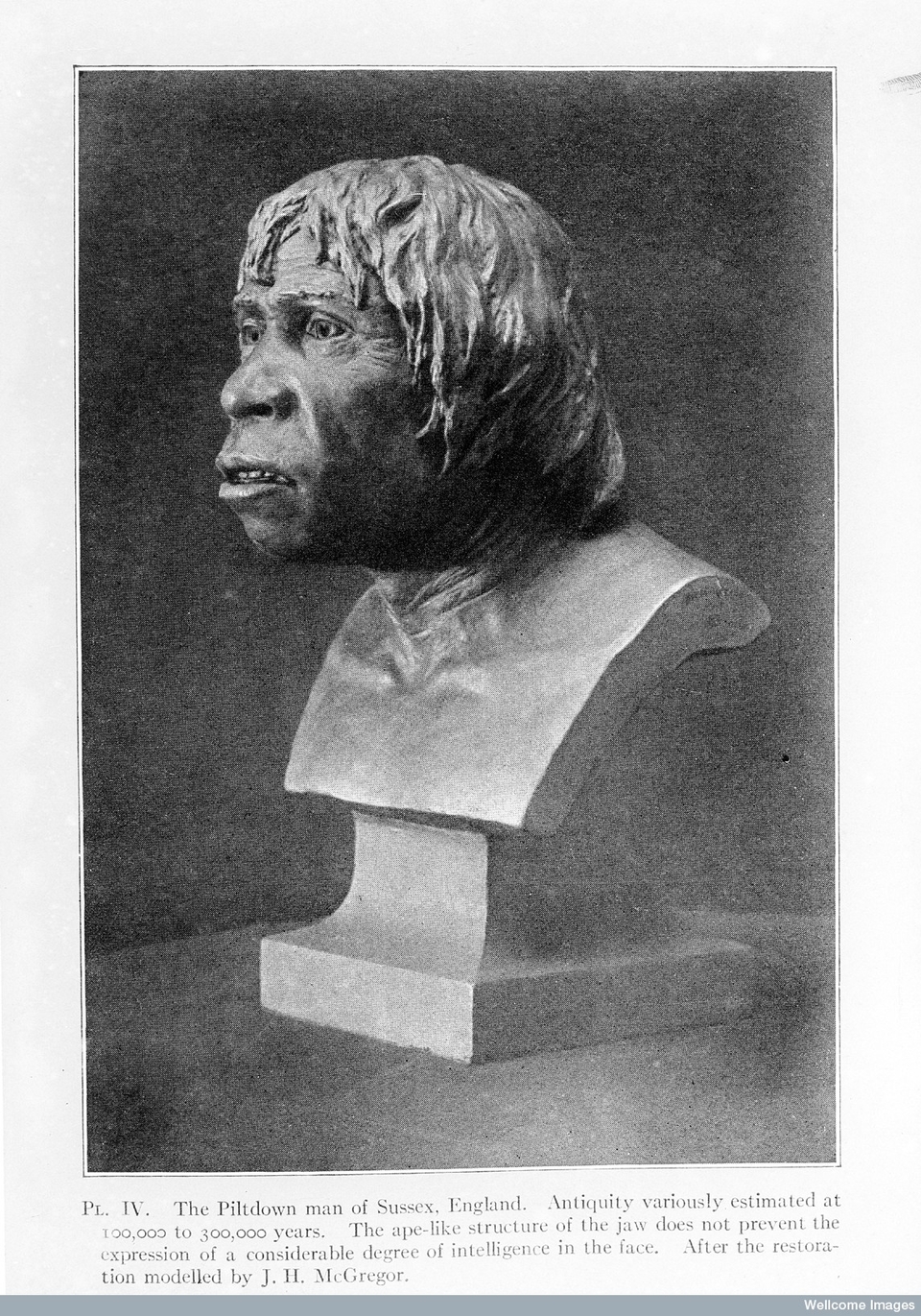

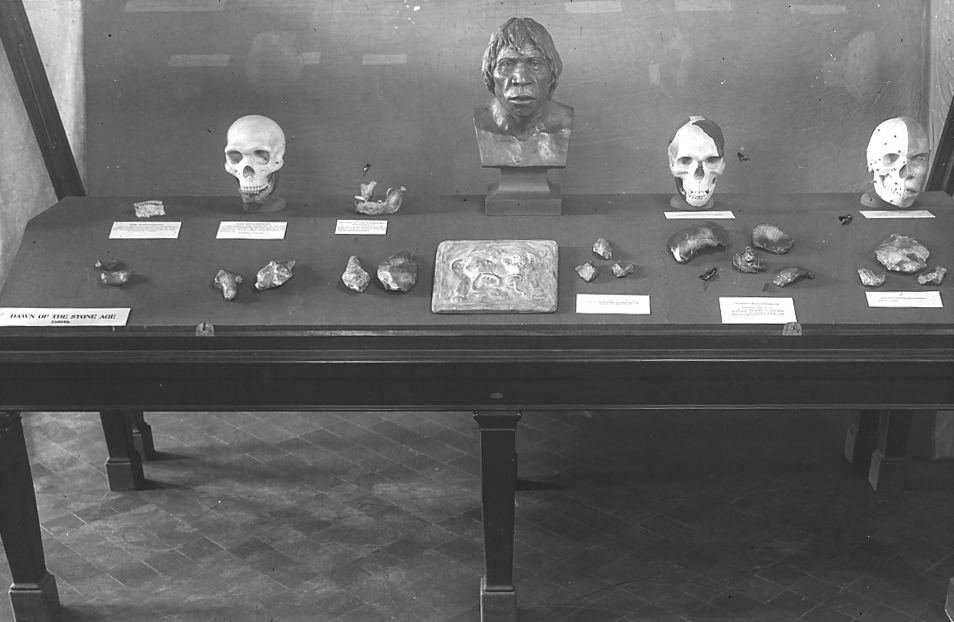

Aimé Rutot’s reconstruction of the Piltdown, Eoanthropus dawsonii. Card from Keystone View Company, 1920s. Still tracking down the museum that ran this exhibit...

Piltdown’s celebrity status was cemented almost immediately upon its discovery. More than just a headline and curiosity, the fossil quickly found its way into museum exhibits through casts and reconstructions and the scientific literature surrounding the fossil flourished. While sketches and inked reconstructions of the fossil abounded, by the 1920s, Aimé Rutot’s reconstruction of the Piltdown hominin – holding the artifact colloquially called the “cricket bat” – was de rigour for early twentieth-century Early Man museum exhibits.[2]

Rutot’s reconstruction pushed public awareness of the fossil even farther when Keystone View Company included Piltdown as one of the stereo cards in their Biology Unit as a teaching tool.

Using a stereopticon to view the Keystone Piltdown card and ponder Rutot's reconstruction.

The stereoscope was an important tool for laboratory and scientific work in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries for a variety of scientific disciplines, including paleoanthropology. The stereoscope expanded what a researchers was able to “see,” and “how” they were able to see it, in the same way that telescopes and microscopes expanded the visual possibilities for other sciences centuries before. A stereoscopic plate contains two slightly offset views of the same image and these images line up with the viewer’s left and right eyes. Thanks to power of binocular vision, the brain “combines” these two images into one, creating the illusion of three-dimensional depth. (For more about the stereoscope and early paleoanthropology research, check out 3D Neanderthals at Public Domain Review[3].)

This specific card, however – Evolution, Early Man: Piltdown – puts the Piltdown fossil squarely in the public’s eye on two levels. Not only does Rutot’s reconstruction put a face on the fossil, the Keystone stereo cards reinforced the accessible nature of a stereo image – there wasn’t any scientific expertise needed to use the instrument or to interpret the image present. (The stereoscope – and stereopticon – was, more often than not, regarded by earlier Victorian audiences as a “philosophical toy” – much like a kaleidoscope or a zoetrope. “The stereoscope is now seen in every drawing room; philosophers talk learnedly about it, ladies are delighted with its magic representations, and children play with it,” noted Robert Hunt a British photo-chemist.[4])

The bits of Piltdown’s own material culture – like the stereo card – speak to the celebrity and staying power of the fossil over the last century.

And a big thanks to @Chris_Manias for feedback about the Piltdown exhibit!

Further Reading:

[1] The wealth of literature that surrounds Piltdown is astonishing. For a quick read, check out Lydia Pyne, “Piltdown Man: Untangling One of the Most Infamous Hoaxes in Scientific History—Blog,” The Appendix

[2] Raf De Bont, “The Creation of Prehistoric Man: Aimé Rutot and the Eolith Controversy, 1900–1920,” Isis 94, no. 4 (December 2003): 604–30, doi:10.1086/386384.

[3] Lydia Pyne, “Neanderthals in 3D:L’Homme de La Chapelle,” The Public Domain Review, February 11, 2015, /2015/02/11/neanderthals-in-3d-lhomme-de-la-chapelle/.

[4] Robert Silverman, “The Stereoscope and Photographic Depiction in the 19th Century,” Technology and Culture 34, no. 4 (October 1993): 729–56.